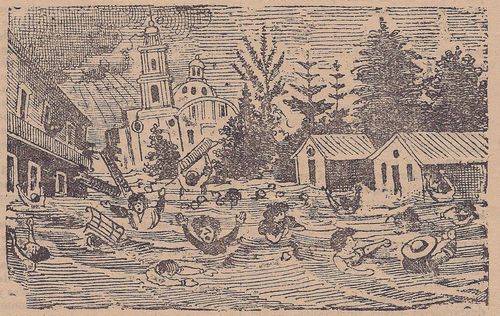

Original edition of the Gaceta Callejera titled "Terrible Inundacion en las Ciudades de Malaga, Veloz y Pueblo del Colemar Mas De 200 Ahogados Muchas Familias Sin Hogar " (Terrible Flood in the Cities of Malaga, Veloz And the Town of Colemar More Than 200 Drowned Many Families Homeless) with etchings by Jose Guadalupe Posada. Published by the shop of Antonio Vanegas Arroyo in Mexico City in 1907. Part of the Jean Charlot collection at the University of Hawaii. Sensational news such as the great flood of Malaga in 1907 travelled across borders and continents. In this case we find this broadside that tells the horrific tragedy of what happened in Andalucia, Spain on September 26, 1907.

Torrential rains, estimated to have been around 300mm in just 24 hours, triggered flash floods that swept through the region, catching many people off guard. Malaga, a coastal city, was particularly hard hit as the floodwaters surged through the streets, inundating homes and businesses. The Guadalmedina River, which runs through the city, overflowed its banks, exacerbating the flooding. Veloz and Colemar, two smaller towns located inland, were also severely affected. The floods destroyed bridges, roads, and other infrastructure, leaving many people stranded and isolated.

The death toll from the floods reached over 200, with many more injured or missing. The majority of the fatalities occurred in Malaga, where the floodwaters were most intense. The disaster left a deep scar on the region, and the memory of that fateful day still resonates in the communities affected. In the aftermath of the floods, the Spanish government declared a state of emergency and mobilized resources for rescue and relief efforts. The King of Spain, Alfonso XIII, even visited the affected areas to offer his condolences and support. The reconstruction process was long and arduous, but the communities eventually rebuilt their homes and lives.

In the early 1900s, print shops like the one run by Antonio Vanegas Arroyo capitalized on major tragedies, such as the devastating floods in Andalucia, to sell their broadsheets to the public. These broadsheets, also known as corridos or relaciones, were single-sheet publications that combined sensationalized news with eye-catching illustrations made by famously made by Posada and Manuel Manila to capture the attention of a largely illiterate population.

Print shops like Vanegas Arroyo's recognized the public's fascination with tragic events and used it to their advantage. They would quickly produce broadsheets detailing the disaster, often exaggerating the death toll and embellishing the narrative with dramatic language and imagery. These broadsheets were then sold on the streets by voceadores, or street vendors, who would loudly proclaim the headlines and attract curious onlookers. The broadsheets served as a form of mass communication in a time when newspapers were not widely accessible. They provided a glimpse into the events of the day, albeit often sensationalized, and satisfied the public's appetite for dramatic stories. The tragic events themselves became a commodity for print shops, allowing them to profit from the public's interest in the macabre and sensational.

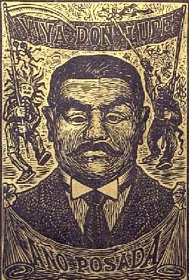

Jose Guadalupe Posada

(1852 - 1913)

Considered to be one of the best engravers in Mexico´s history. Compared by some to Honoré Daumier for his merciless satire of bourgeois life, Aubrey Beardsley who illustrated Oscar Wilde's Salomé, and political cartoonists as Herbert Block (Herblock) who took on McCarthyism and Stalinism. Posada was born in Aguascalientes on February 2, 1852. His brother Cirilo, the town's schoolteacher taught him to read, write and draw. He started drawing and copying religious images at an early age and worked in a ceramic workshop before learning the art of engraving. In 1866 he started working as an apprentice at the Taller de Trinidad Pedroza where he learned lithography and engraving. This experience helped him make a few satirical illustrations for "El Jocote" magazine.

In 1872 his satires of Jesús Gómez Portugal (a regional boss or cacique) became the first to produce repercussions. Gómez forced Posada and Pedroza to move to Leon Guanajuato where they started to produce their own lithographs and prints in wood that would illustrate matchboxes, documents and books. After a flood destroyed most of León in 1887 he decided to move to Mexico City, where he went to work for Irineo Paz, grandfather of Nobel Prize winning author Octavio Paz. He opened two additional workshops and also drew political cartoons for many periodicals. His dedication to his work became legendary. A short time later, he became the head artist at the Taller Antonio Vanegas Arroyo, where he made thousands of illustrations for this press that produced inexpensive literature for the lower classes. They printed various newspapers as well as comedies, farces, thrillers, songbooks and histories of saints and historical figures. He also made illustrations and political caricature for other editorials like "Argos", "La Patria", "El Ahuizote" and "El Hijo del Ahuizote", where they would oppose the current government run by Porfirio Díaz. He is reported to have worked for over 50 different publications in all. Posada worked closely with Manuel Manilla and Constancio Suarez (poet) to produce rich editorials against the dictatorship. Along with Manilla, he became the greatest promoters of the tradition of the Day of the Dead, celebrated November 2 in Mexico. Posada´s most notable work is the "Catrina" where a skeleton is dressed up in the fanciest clothes of the time to represent the corrupt society under which he lived. It was this theme that got him national recognition and even landed him in jail a few times. From the outset of the Mexican Revolution of 1910 and up until his death on January 20, 1913, Posada produced countless prints for the workers press where he established his notoriety becoming an influence on other artists such as José Clemente Orozco, Leopoldo Mendez and the Taller de Grafica Popular. There are major collections of his works at the Bellas Artes National Institute, the Biblioteca de Mexico ("Library of Mexico"), the National Library of Anthropology and History and the Municipal Archive of the city of Leon, the art collection at the Basilica de Guadalupe in Mexico City, the Getty Research Institute, the Art Institute of Chicago, the University of Hawaii, the University of New Mexico and the Library of Congress.